Using the Linux Terminal

The Linux command line is a text interface to your computer. Often referred to as the shell, terminal, console, prompt or various other names, it can give the appearance of being complex and confusing to use. However, the basics are actually quite simple and easy to learn.

Side note: If you are interested in learning more about the history of the terminal, read Section 1.2.1 for more information.

Accessing the Terminal Over SSH

Most of you are probably running Windows or MacOS on your personal computer, so you will need to access a linux terminal remotely using a Secure Shell (SSH) connection. On Windows, you can do this using MobaXTerm, PuTTY, or WinSCP. Read Section 1.3 for more information on how to access CSU's Linux servers.

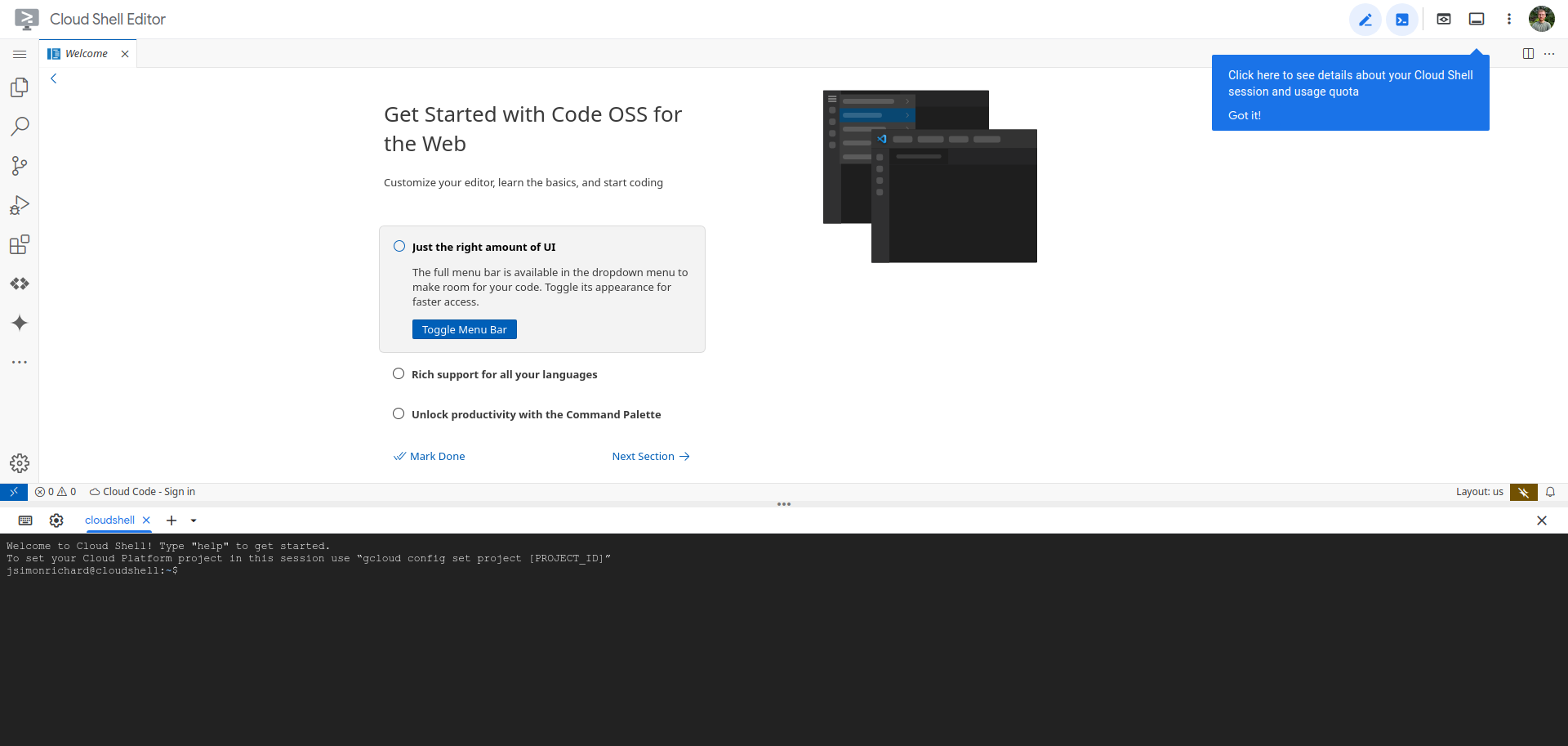

Using Google Cloud Shell

You also have the option of using Google Cloud Shell, which is free. Simply go to https://shell.cloud.google.com/. After the shell is provisioned, you should see the environment below:

Your linux shell should be available at the bottom of the page.

Running your First Command

To run your first command, click inside the terminal window to ensure it's active, then type the following in lowercase and press Enter:

pwd

This will display your current directory path (likely something like /home/YOUR_USERNAME), followed by the prompt text again.

The prompt indicates the terminal is ready for your next command. When you see references to "command prompt" or "command line," they simply mean the place where you type commands in the terminal.

When you run a command, any output will typically appear in the terminal. Some commands display a lot of text, while others may not show anything if they complete successfully. If a new prompt appears right away, the command likely succeeded.

Navigating the Linux Environment

The Linux Essentials

-

The

pwdcommand (print working directory) shows your current location in the file system. The working directory is where file operations take place by default unless specified otherwise. To check where you are, usepwd. -

To see other directories available from the directory that you are in, use

ls. -

To autocomplete a directory or filename, type the first couple letters and then hit

tab. If there are multiple files that start with those letters, nothing will happen, hittabagain and it will show all the available files that start with those letters. -

A quick way to run similar commands to the one you just ran is to hit the up arrow, which will autofill the previous command, and then you can make a small change and run it again. The up arrow accesses a history of all the commands you've used recently, so you can keep hitting it to see previous commands.

-

Pressing

ctrl+cat any time will interrupt the current execution, if there is any, and return to the command line. This is useful for running C programs, especially if you run into an infinite loop. Just executectrl+cand it will stop.

To change the working directory, use cd (change directory):

-

Move to the root directory:

cd / pwd -

Move to the "home" directory from root:

cd home pwd -

Go up one level to the parent directory:

cd .. pwd -

Just one

.is used to refer to the current directory. This will be useful later on when we are moving files between directories. -

To return to your home directory (also represented by the

~path):cd pwd

You can also move up multiple levels:

cd ../..

pwd

To go directly to the "etc" directory from your home directory:

cd # this is same as cd ~

cd ../../etc

pwd

Paths can be relative (depending on your current directory) or absolute (starting with /).

Most examples so far have used relative paths, meaning the location you navigate to depends on your current directory. For instance, moving to the "etc" directory works from the root:

cd /

cd etc

But if you're in your home directory and try cd etc, you'll get an error because the command is relative to your current location.

Absolute paths, however, work regardless of your current directory. These paths start with a /, indicating the root directory. For example:

cd /etc

This will always take you to the "etc" directory, no matter where you are. Similarly, running cd alone returns you to your home directory. Another absolute path shortcut is using ~, which refers to your home directory:

cd ~

cd ~/Desktop

Creating and Opening Folders and Files

To safely experiment with files, let's create a directory away from your home folder:

mkdir /tmp/tutorial

cd /tmp/tutorial

This creates a new directory, "tutorial," inside /tmp using an absolute path. Now, let's create a few subdirectories:

mkdir dir1 dir2 dir3

This command creates multiple directories at once. If you'd like to create nested directories, use the -p option (short for "make all Parent directories"):

-pis what is called an "option". Most linux commands have options, ways to customize the implimentation or scope of the execution of that command. To see a list of all of the options associated with any command, type that command followed by--helpand you will get a list of the available options along with a brief description of each.mkdir --help

mkdir -p dir4/dir5/dir6

Here, -p ensures parent directories (dir4 and dir5) are created if they don't exist.

To create folders with spaces in the names, use quotes or a backslash to escape the space:

mkdir "folder 1"

mkdir folder\ 3

Avoid spaces in file names where possible by using underscores or hyphens for easier command-line use.

Listing and Creating Files

Let's create some files and work with them. Start by listing the contents of your current directory:

ls

To capture the output of this command into a file, use redirection (>):

ls > output.txt

This creates a file called output.txt with the list of directory contents. To view the file:

cat output.txt

The echo command can also create files with content:

echo "This is a test" > test_1.txt

echo "This is a second test" > test_2.txt

echo "This is a third test" > test_2a.txt

You can view their contents using cat. To combine multiple files:

cat test_1.txt test_2.txt test_2a.txt > combined.txt

cat combined.txt

Wildcards simplify commands when file names follow patterns.

?will accept any filename with just one character that follows that pattern before the?- So using just

?will grabtest_1andtest_2but nottest_2a

- So using just

*will accept any filename with any amount of characters that follows the pattern before it, so long as it begins with the preceding name.- This will grab all three files, since they all follow the same initial pattern

cat test_?.txt

cat test_*

If you want to append text to an existing file, use >>:

echo "Appending a line" >> combined.txt

cat combined.txt

To view long files one page at a time, use less:

less combined.txt

You can navigate each line using arrow keys, or b and spacebar to go up down entire pages, and exit with q. This basic workflow helps in creating and managing files with content efficiently.

Vim & Nano

These tools are complex enough to deserve entire pages of their own, but just to get your toes wet, if you'd like to properly edit files in the terminal, you can do so using the nano or vim commands. These commands will start the nano or vim programs, and you will not be able to use normal linux commands. Don't panic!

nano combined.txt

or

vim combined.txt

- To exit nano, hit

ctrl+x - To exit vim, type

:qand thenenter

Case Sesitivity

Unix systems are case-sensitive, meaning files like A.txt and a.txt are treated as entirely different. For example:

echo "Lower case" > a.txt

echo "Upper case" > A.TXT

echo "Mixed case" > A.txt

This creates three distinct files. It’s best to avoid file names that only differ by case to prevent confusion, especially when transferring files to case-insensitive systems like Windows. There, all three names would be treated as the same file, which could lead to data loss.

Rather than relying on upper case names (which would require frequent Caps Lock toggling), many users stick to lower case file names. This prevents case-related issues and keeps typing consistent with most shell commands, which are lower case. This habit helps avoid complications and reduces the chances of filename collisions.

Nope, don't wanna Shout.

A good practice for file naming on Unix systems is to use only lower-case letters, numbers, underscores, and hyphens. File names typically include a dot followed by a few characters as the file extension (e.g., .txt, .jpg). Sticking to this pattern avoids issues with case sensitivity and escaping, and simplifies command-line usage. Although it may seem limiting, this approach will save time and prevent errors when working in the terminal regularly.

File Manipulation

Moving Files:

- To move a file into an existing directory:

mv combined.txt dir1 - You cannot move files into a directory that does not exist yet! You must first use

mkdirto create the directory for which you'd like to move your file to - To move the file back to the current directory:

mv dir1/combined.txt . - We can use the

*character to move everything from one directory to another:mv dir1/* .

Moving Multiple Files:

- To move several files and directories at once:

mv combined.txt test_* dir3 dir2

Moving Across Nested Directories:

- To move

combined.txtfrom one directory to another nested location:mv dir2/combined.txt dir4/dir5/dir6

Copying Files:

-

To copy a file from one location to the current directory:

cp dir4/dir5/dir6/combined.txt . -

To create a copy with a different name:

cp combined.txt backup_combined.txt

Renaming Files:

- To rename

backup_combined.txttocombined_backup.txt:mv backup_combined.txt combined_backup.txt

Renaming Directories:

- To rename directories (use the Up Arrow for quicker edits):

mv "folder 1" folder_1 mv "folder 2" folder_2

Use ls to verify the results of each operation. These commands help manage files and folders efficiently without needing to change directories or use the mouse.

Deleting Files:

- To delete files:

rm dir4/dir5/dir6/combined.txt combined_backup.txt

Deleting Directories:

- To delete directories, use

rmdirfor empty folders:

rmdir folder_*

- If a directory contains files or subdirectories,

rmdirwill fail. To delete non-empty directories, usermwith the recursive-roption:

rm -r folder_6

This is a quick and efficient way to clean up files and folders without unnecessary repetition.

Safety Warning

When using the rm command, be extremely cautious, as it permanently deletes files without moving them to a trash folder. Accidental deletions can easily occur, especially when using wildcards. For example, rm t* deletes all files starting with "t," while rm t * could delete everything in the directory.

To prevent unintended deletions, consider using the -i (interactive) option with rm. This option prompts you to confirm each deletion, allowing you to type Y to delete, N to keep, or Ctrl-C to cancel the operation. Always double-check your commands before executing them to avoid irreversible loss.

Recursive Deletion:

Be especially cautious when using rm -r, as it will delete everything within the directory, including all files and subdirectories. It’s often safer to explicitly delete files first and remove the directory afterward.

Piping

Modern computers and phones have advanced capabilities, yet text remains crucial for organizing files, from filenames to metadata. The Linux command line offers powerful tools for text manipulation, particularly through piping, which allows the output of one command to feed directly into the input of another.

Piping examples:

- Count Files in a Directory:

To count the number of lines in an output without creating a temporary file (which is required for

>redirection), use:

So here,ls | wc -llsreturns a list of all the files in your current directory, and then sends that list towc -l, which counts the lines of text, which will be the number of items in your directory. - View Large Outputs:

For lengthy outputs, use

less:

Again, output ofls | lesslsgoes toless - Find Unique Lines:

To count unique lines in

combined.txt, chain commands:

This will not remove all duplicates, becausecat combined.txt | uniq | wc -luniqonly removes adjacent duplicates. - Sort Before Uniquing:

To prepare for using

uniq, sort the file first, which will put all duplicates next to each other:sort combined.txt | uniq | wc -l - Searching for a string in an input:

To search for a string in a file, use

grep:cat combined.txt | grep "string" - Check Command Documentation:

Use the

mancommand for the manual, or the full details on how commands work:man uniq